Easier to build, Easier to replace?

Software of value must become something near to a capability you operate

An active seat was the cleanest SaaS lie.

It looks like adoption. When it expands it sure feels like progress. In many cases it has renewed like inevitability. Why was it so clean? Because it has let vendors tell a simple story: more active users equals more value and it lets customers repeat that story back. “We’ve now standardized on the tool.”

But seat consumption has rarely proved that the customer made more money or spent less money.

The machinery built around this proxy with multi-year contracts, renewal gamesmanship and NRR as religion has trained our entire Tech industry to optimize capturing value rather than creating it.

I repeat: we’ve been trained to capture value more than to create it.

The modern enterprise stack is full of software that is “in use” the way a gym membership is “in use”1. It exists, it’s paid for, it’s occasionally visited, and it provides a comforting sense that something healthy may be happening.

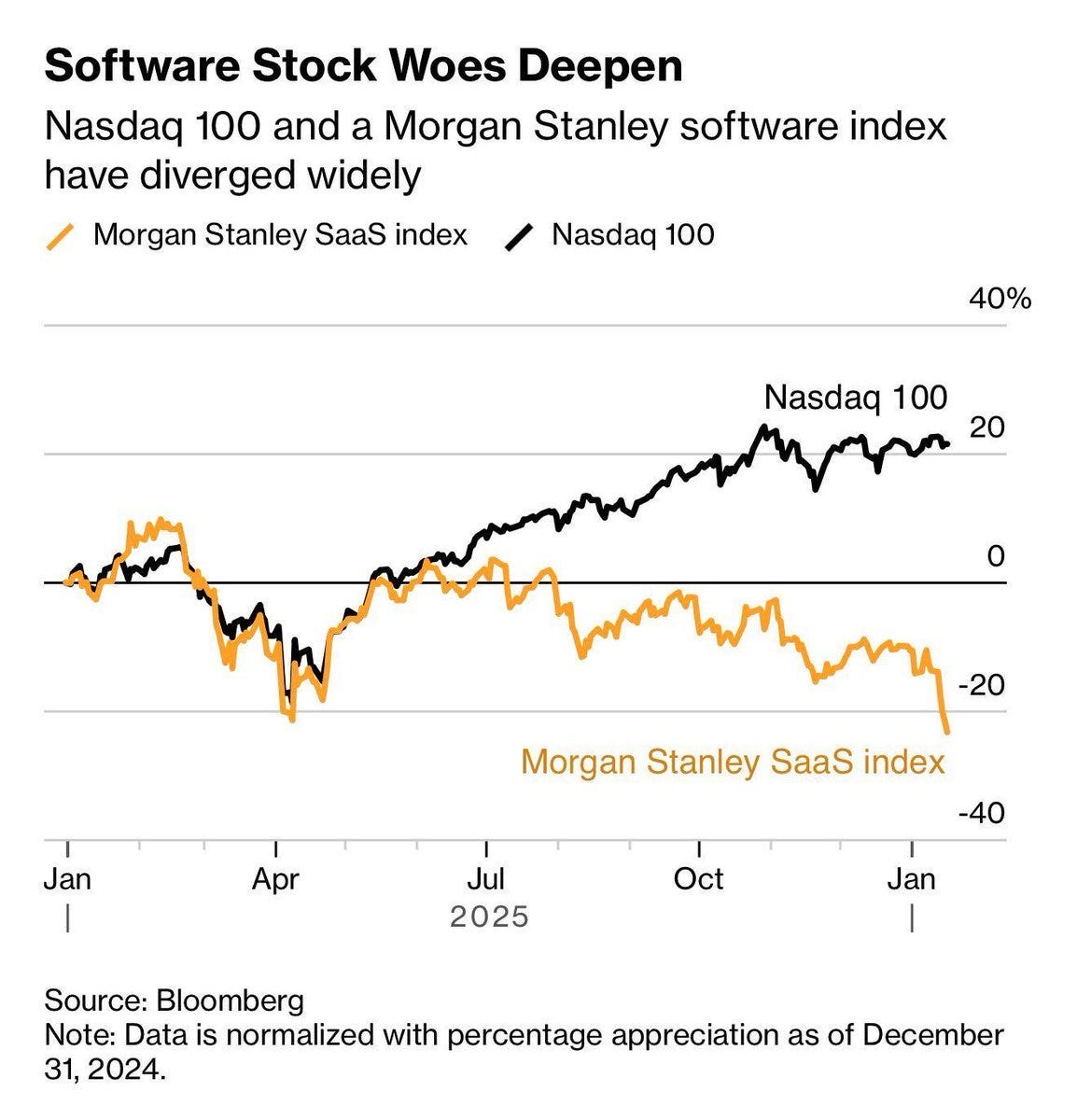

That’s why the question of this particular meditation matters. It isn’t because generating code is suddenly trivial. But rather due to the fact the illusion that usage implies outcomes is becoming harder to maintain. No place more clearly evidenced than by the fact that SaaS multiples have completely disconnected from the rest of the Nasdaq… which some have been calling The Great SaaS Meltdown.

How We Got Here

The original promise of SaaS was boring and honest. Software delivered over the internet would be easier to deploy, easier to update, and less painful to run. It was a delivery model that also happened to collapse distribution and maintenance costs.

Then venture capital (and later private equity) discovered that recurring revenue commanded higher valuation multiples than one-time sales and like that SaaS became a business model2.

This happened under specific economic conditions from 2009 to 2022 (“ZIRP”) when interest rates hovered near zero. Capital was cheaper than it had been in living memory. Growth-at-all-costs was the rational response to this low cost of capital. Reid Hoffman’s blitzscaling doctrine made sense when you could raise endless rounds to cover losses while you captured market share. The companies buying software operated under similar logic: budgets were loose, CFOs were measured on growth initiatives, and shelfware? Well maybe that is an accepted cost of doing business.

And so multi-year contracts priced by the seat became de rigueur: software was relatively scarce and expensive to build, switching could be risky, IT bandwidth was constrained, and standardization was itself a win even if in most cases the tool was mediocre. Under these conditions the difficulty of leaving could look a lot like desire to stay.

A tool that genuinely transforms a business and a tool that sits half-used can generate the same revenue for the vendor. This particular unit of value is detached from value itself.

If they’ve made a mistake, correct them gently and show them where they went wrong. If you can’t do that, then the blame lies with you. Or no one. — X. 4

I’ll Happily Say It: Usage-Based Billing Isn’t the Answer

AI companies have recently made metering fashionable again because the new cost structure forces honesty. We know that every token costs money. But usage-based billing isn’t new. Telecom did it. Cloud did it. Metering aligns vendor revenue with vendor cost. This is not the same as aligning vendor revenue with customer outcomes.

To flip the above statement from the vendor’s perspective, a product can be heavily used and still be wasteful. A product can be lightly used and still be transformative. The difference is whether it’s directly attributable to revenue gained or costs reduced and not whether it generated “time saved” anecdotes in a quarterly business review.

Time saved is only value if it converts to something the business can measure: fewer heads, more throughput, fewer errors, faster cash conversion, higher win rates, lower churn, lower loss ratios, lower downtime. Otherwise it’s a story that makes everyone feel modern and sexy while financial statements do not meaningfully change.

Easier to build, easier to replace

Quoted below is a very common argument in light of the following statement: as software becomes easier to build, enterprises will stop buying it and generate whatever they need on the fly.

Enterprises don’t buy software because code is hard. They buy standardization, shared context, institutional memory. Vendors absorb complexity. A trucking company’s advantage is logistics, not maintaining internal tools. Even if software becomes trivially easy to build, enterprises won’t become perpetual hackathons.

The part that’s right: Enterprises really do buy reliability, governance, auditability, and continuity. They buy a tool that keeps working when the champion leaves. “Shared context and institutional memory” is real. It shows up as fewer local variations, fewer shadow processes, fewer “mission-critical spreadsheets.” Standardization reduces coordination costs across teams and time3.

The part that’s wrong: The leap from “standardization matters” to “per-seat subscriptions represent value” is where the argument collapses.

A vendor can absorb complexity and still be a massive tax. The claim that vendors absorb complexity is true but incomplete since vendors also create complexity. The integration layers, the API rate limits, the permission structures, the upgrade cycles these are very far from natural phenomena.

They’re artifacts of dependency engineering: features and workflows designed to make the product hard to replace, because retention celebrates stickiness without asking whether stickiness comes from love or from pain.

Salesforce has spawned an entire ecosystem of implementation partners precisely because the platform’s complexity exceeds what most organizations can manage internally4. The consultants aren’t absorbing inherent complexity; they’re absorbing Salesforce-specific complexity that exists because it serves Salesforce’s interests.

Enterprises won’t turn core operations into weekly experiments. But they will replace software faster when replacement stops being a multi-quarter migration and becomes a credible option. AI doesn’t need to make all software trivial. It just needs to collapse the switching cost curve enough that vendors must justify themselves in outcomes, not inertia.

What Changes When Building Gets Cheaper

When software becomes cheaper to produce, you don’t get a world without vendors. It’s just you get a reframed world where defensibility moves5.

The vulnerable categories are the ones where the “product” is mostly CRUD, dashboards and templates… things that were sticky because they were annoying to recreate, not because they were uniquely valuable. The first casualties are tools whose differentiation is “we assembled the obvious features and sold it as a product platform”.

The survivors deliver one of these:

Provable economic impact: revenue lift, cost reduction, risk reduction that can be measured, not asserted.

Operational reliability at scale: uptime, security, compliance that would be genuinely hard to replicate.

Network effects: shared data that compounds like context used to power the business, fraud signals, marketplace liquidity.

Deep integration: real orchestration across messy systems and not just another fragile API connector.

Accountability: someone is on the hook when it breaks.

In my view, the Software must become something near to a capability you operate and not something you just license.

The Return of Skin in the Game

Before Software ate the world, serious money in enterprise transformation often came from a simple structure: the provider got paid when the client got results. AI makes that model plausible again because delivery can be faster and more adaptable.

We know Palantir and their forward-deployed engineers embed with the customer to solve their specific problem by building exactly what the customer needs (and then arbitraging these insights into Palantir’s core products and their data ontologies). This approach has been derided as “unscalable” by observers who had internalized SaaS economics as natural law. But Palantir’s customers have renewed because the software worked and not because switching was painful.

The product then must not just be software. It’s implementation, integration, change management, and measurement. Compensation that ties to a defined outcome: incremental gross margin, reduced handle time that actually reduces staffing, reduced fraud loss, increased conversion, shortened quote-to-cash cycles or in Palantir’s case… well dare I say6.

Real value-aligned pricing means defining a metric the CFO cares about, measuring it honestly, and letting the vendor’s economics hurt if improvement doesn’t happen. Many SaaS vendors don’t want this because it would reveal that their product doesn’t actually have any true value.

The Human Cost

The SaaS economy has built careers for millions myself included. Customer success managers. Implementation consultants. Sales engineers. Salesforce administrators. Integration specialists. An entire professional class whose expertise is deep knowledge of specific platforms much of which becomes worth a whole lot less if the platform becomes replaceable or is obviated.

But know this! The enterprises buying software are not innocent either. They are willing participants in subscription theater. Often they preferred the comfort of the renewal over the accountability of outcomes. They let “we’re standardized on X” substitute for “X is making us money.” The reckoning is for everyone who found it easier to pay for the illusion of progress than to measure real results. And then do something about it.

So…

Easier to build does mean easier to replace. But not in the way that many breathless predictions suggest.

Enterprises won’t become perpetual hackathons. They won’t generate software on the fly for every need. Standardization, reliability, and institutional memory matter.

What changes is simply that pricing proxies are exposed. When building and modifying software gets cheaper, the burden shifts to proving that what you ship creates measurable economic change. Seats, “adoption,” renewals-as-success these worked when switching was expensive enough that no one tested whether the value was real and is a condition that is ending.

The future is fewer vendors selling access and more vendors selling accountability.

If your product could be rebuilt in a weekend, you need to be selling something beyond the code itself and its one of these three things:

A system that keeps other systems working

A capability that integrates across messy reality, or

An outcome you’re willing to guarantee.

If you can’t claim one of those, what you’re actually selling and trying to retain is the customer’s switching cost: their sunk investment, their migration pain and their fatigue. That’s inertia. And inertia was always a depreciating asset.

The next time you sign a renewal, ask the vendor a simple question: what will you give back if nothing improves?

Their silence will tell you everything.

An anecdote: at my last company we did a comprehensive audit of our SaaS spend in ~2023 timeframe. For a company of 2000 we were paying more than 300 SaaS vendors over $30M a year. Of course there was a power law distribution of those vendors that represented the majority of that spend and you can likely name them… but still, talk about a lot of gym memberships!

Of all written on this massive topic I personally like Subscribed by Zuora CEO Tien Tzuo. But despite its merits it still draws attention to my point re: the tension between earning customer loyalty versus manufacturing customer inertia.

There are many such studies but this one found that workers on average spent more than 58% on coordinating their work versus 42% of time doing it… the cause MEETINGS.

If you’ve ever been through a Salesforce migration before I empathize deeply with you. I was involved in two back to back and I’d rather eat dirt than have to do it again.

This is a small example but a relevant one: at my current SpecStory, I recently migrated our hosted product documentation from mintlify.com to an implementation I built in a day. I did so because mintlify and others like are hardly defensible when open source libraries like fumadocs alongside agents like Claude Code can help you build documentation clones of statically rendered sites can be seamlessly deployed on Vercel for essentially $0. To spread the love I open sourced this as unmint.dev read about it here and try it out here.

You can read about the controversies here

This is genuinely one of the most clear-eyed takes on the SaaS reckoning I've read. The gym membership analogy is perfect because I've literaly seen teams renew software they havent touched in months just to avoid the migration conversation. The dependency engineering point is underrated too, so much complexity exists to make leaving hard rather than to make staying valuable. Really makes me think differently about renewal negotiations now.