The Intent Gap

It's Software's Original Sin

Software has an original sin and it’s not technical debt.

It’s something deeper, more fundamental, and increasingly urgent as we hand an increasing amount of implementation to AI. It’s the gap between what we mean to build and what we actually do and how that gap is about to become the only thing that matters.

What follows is part cautionary tale, part technical philosophy, and part roadmap for what’s coming.

This isn’t a typical technical essay. And no, you won’t find tips for better prompts. Instead we are going to excavate something more fundamental: the nature of intent itself and why our inability to capture and preserve it has been software’s most expensive problem.

This is a meditation on the space between thought and code: a space that is quickly collapsing. Whether it’s software’s greatest opportunity or greatest threat depends entirely on how well we understand what we’ve been doing wrong all along.

And so we begin our story with every startup’s worst nightmare: building the perfect wrong thing.

The Parable of Three Architects

Together Sarah, Marcus, and Jay sit sullen in the conference room of their once thriving startup. They’d just lost their biggest customer.

“The feature works exactly as designed,” Marcus said, pulling up the spec documents that had evolved over the last eighteen months. “Look, every requirement, checked off.”

Jay nodded. His fingers drumming on the laptop. “The code is clean. Tests pass. Performance metrics are solid.”

Sarah stared at the whiteboard earnestly. It was precisely where they’d mapped the initial customer journey, worked out use cases and later came back to vet them.

Something was wrong with this picture. But she couldn’t quite name it. “Then why did CloudTech just cancel our seven-figure contract” she pondered rhetorically?

The answer came during the exit interview.

“Your invoice reconciliation works,” CloudTech’s CFO said. “Technically”.

“But what we needed was a way to understand our spend. What you delivered was a calculator. The gap is clarity.”

Marcus pulled up the original requirements document. And there it was, in black and white: “System should reconcile invoices across multiple cost centers with 99.9% accuracy.”

“We built exactly what they asked for,” he said.

“No,” Sarah said quietly. “We built what we heard. We built what we thought they meant. We built what was easiest to specify in the Epics we communicated through Jira tickets.”

Jay looked up from his code editor. “So what did they actually want?”

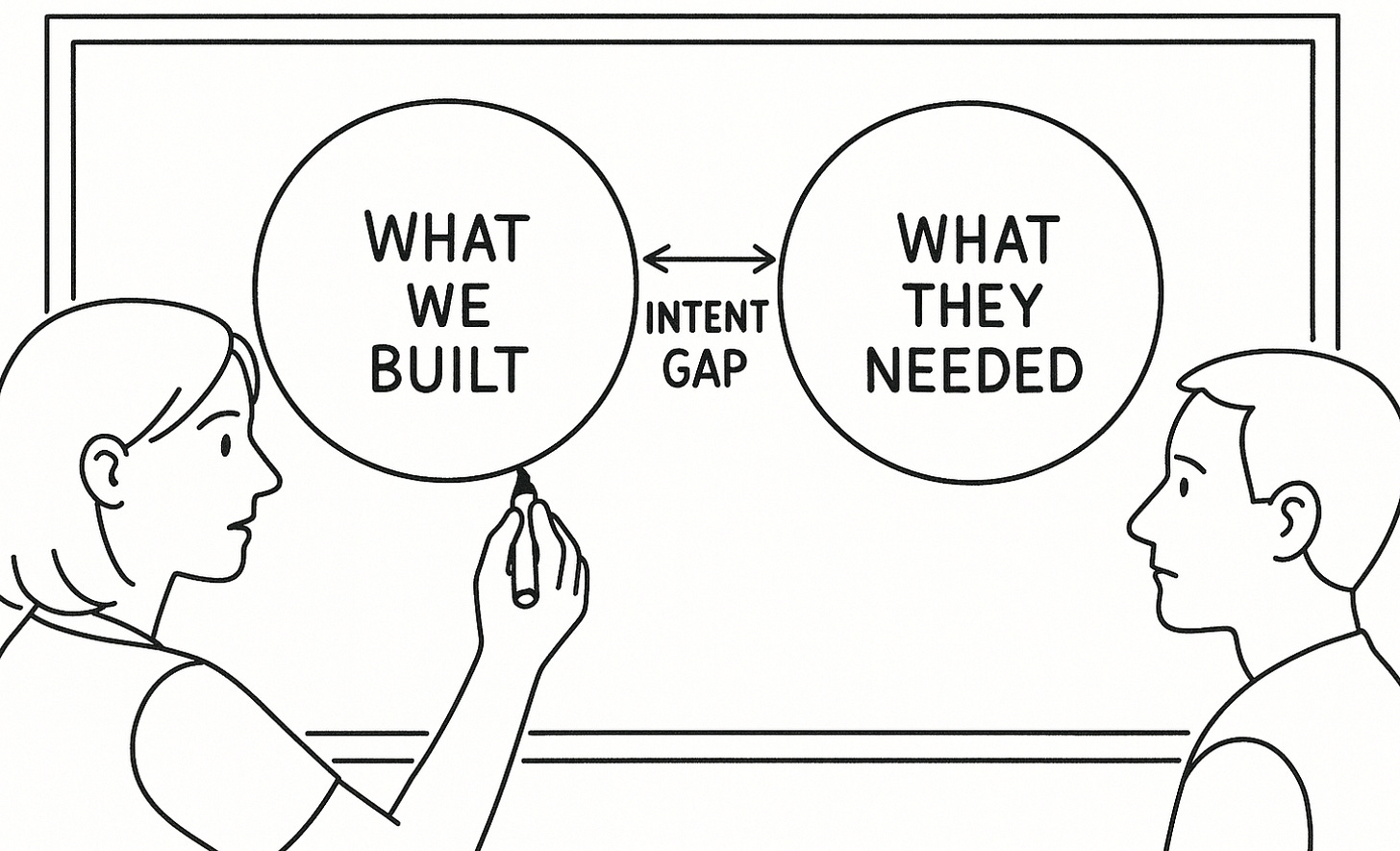

Sarah grabbed a marker and drew two circles on the whiteboard. In one, she wrote “What we built.” In the other, “What they needed.”

The space between them seemed to grow as they stared.

“This gap,” she said, tapping the white space, “this is where we lost them.”

This is the Intent Gap. It’s software’s original sin.

What We Mean When When We Talk About Intent

Intent is the soul of software.

Its that original spark of “what if we could...” that sets everything in motion. But like a game of telephone played through specifications, sprints, and stand-ups, that original intent degrades through each translation.

We’ve developed an entire industry around managing this degradation. Today we call it different things:

Technical debt (when the code diverges from what we meant it to do).

Product debt (when features diverge from user needs).

Design debt (when interfaces diverge from mental models).

Architecture debt (when systems diverge from operational realities).

But these are symptoms of the same disease: The Intent Gap.

To be more precise let’s do some defining.

Definition (software): Intent is the desired state and behavior of a system as conceived by its builders and users—including edge conditions, trade‑offs, and values. Code, configurations, data, and processes are partial, lossy encodings of that intent at a moment in time.

Definition (broader): Intent is direction with meaning. It’s not just what you aim at, but why—the commitments and constraints that shape acceptable ways to get there.

The Gap: Between the intent in our heads and the system in production sits translation loss (ambiguity), temporal drift (intent changes), contextual erosion (people leave, docs rot), and interaction effects (other systems nudge ours off-course). We label the residue technical/product/UX/architecture debt, but those are simply surfaces where the deeper Intent Gap becomes visible.

The Three Translations of Intent

Drawing from my time building products and watching teams struggle with this, I’ve observed how intent gets lost during three critical phases.

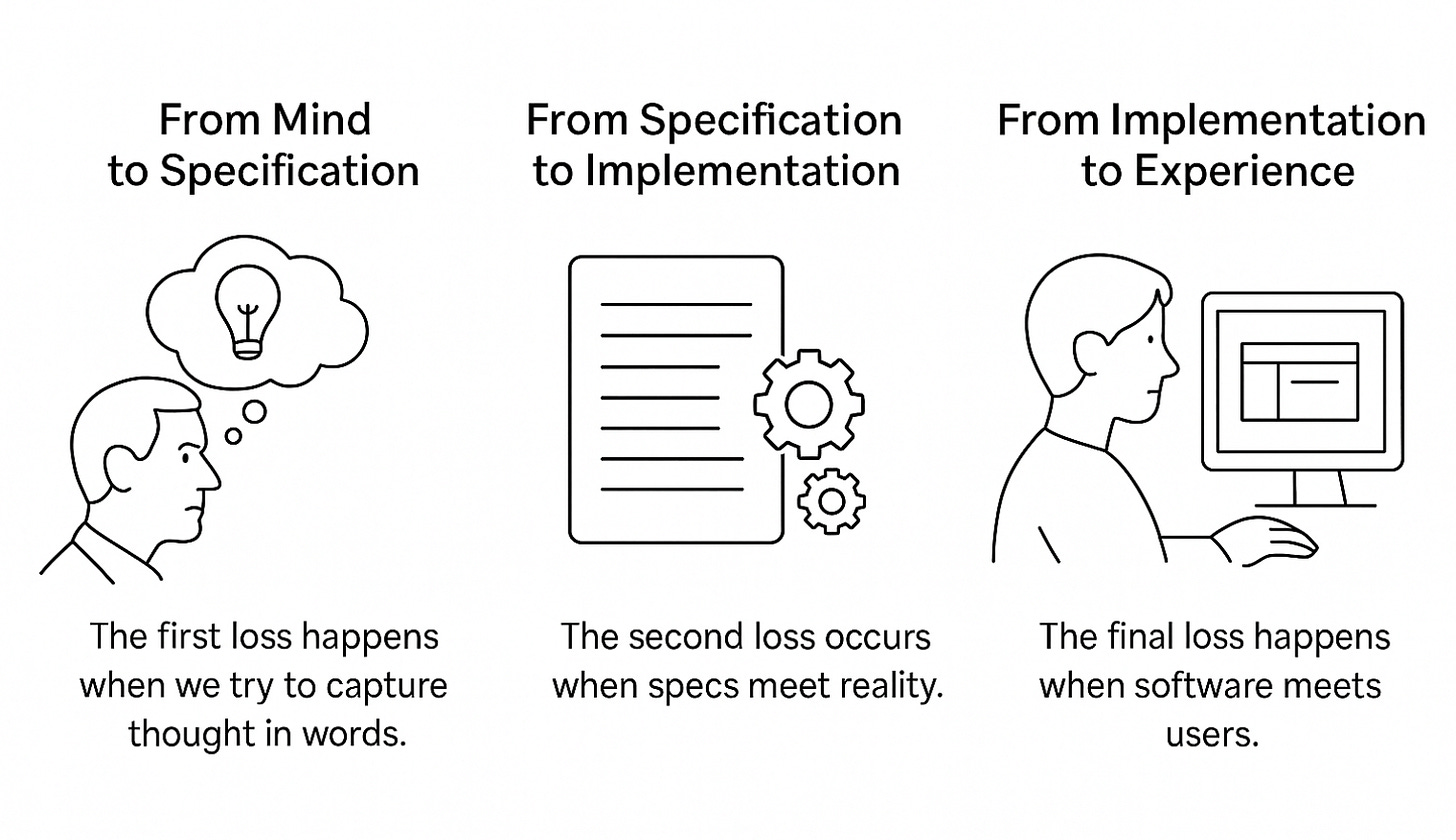

From Mind to Specification The first loss happens when we try to capture thought in words. A founder sees a vision of seamless collaboration. By the time it’s a PRD, it’s become “users should be able to share documents with customizable permissions across workspaces.” The poetry becomes prose. The why becomes what.

From Specification to Implementation The second loss occurs when specs meet reality. That elegant document sharing system? It needs to handle edge cases, scale constraints, security models. Each engineering decision today made implicitly but realized in code is a small betrayal of the original intent, necessary but accumulative.

From Implementation to Experience The final loss happens when software meets users. They don’t care about your elegant behind the scenes micro-services architecture. They care about whether it helps solve their problem so that they get home to dinner on time.

Whats particularly insidious is that Intent Debt compounds faster than all else.

When you build the wrong thing right, you create organizational scar tissue. Teams learn to work around it. Processes calcify.

“That’s just how our system works” becomes the most expensive sentence in software.

I lived this at a prior company where we’d built a sophisticated analytics platform. It could slice data in seventeen dimensions, render real-time visualizations, and scale to billions of events.

There was a glaring problem. Our internal users usually just needed to answer a few simple questions 75% of the time and our interfaces made those questions require more steps than necessary.

We’d optimized for technical capability, not user intent.

Enter the Agents: Intent as a First-Class Citizen

Right now is where the future meets the present and why I believe we’re at an inflection point that makes this meditation urgently relevant.

When we work with Cursor, Claude Code or Codex something fundamental shifts.

Instead of translating our intent through layers of specification, we can express it directly: “I need a way for small teams to understand their AWS spend without becoming cloud economists.”

The agent doesn’t build to a spec. It builds to an intent. And through the initial interaction and all that follow the intent gets clarified, re-reasoned and rationalized.

But here’s the catch: this only works if we get radically better at understanding and expressing intent.

Today’s era where the ability to precisely express intent becomes more valuable than the ability to implement it. But this isn’t about writing better prompts rather it’s about developing a new literacy around what we actually want.

Consider the evolution:

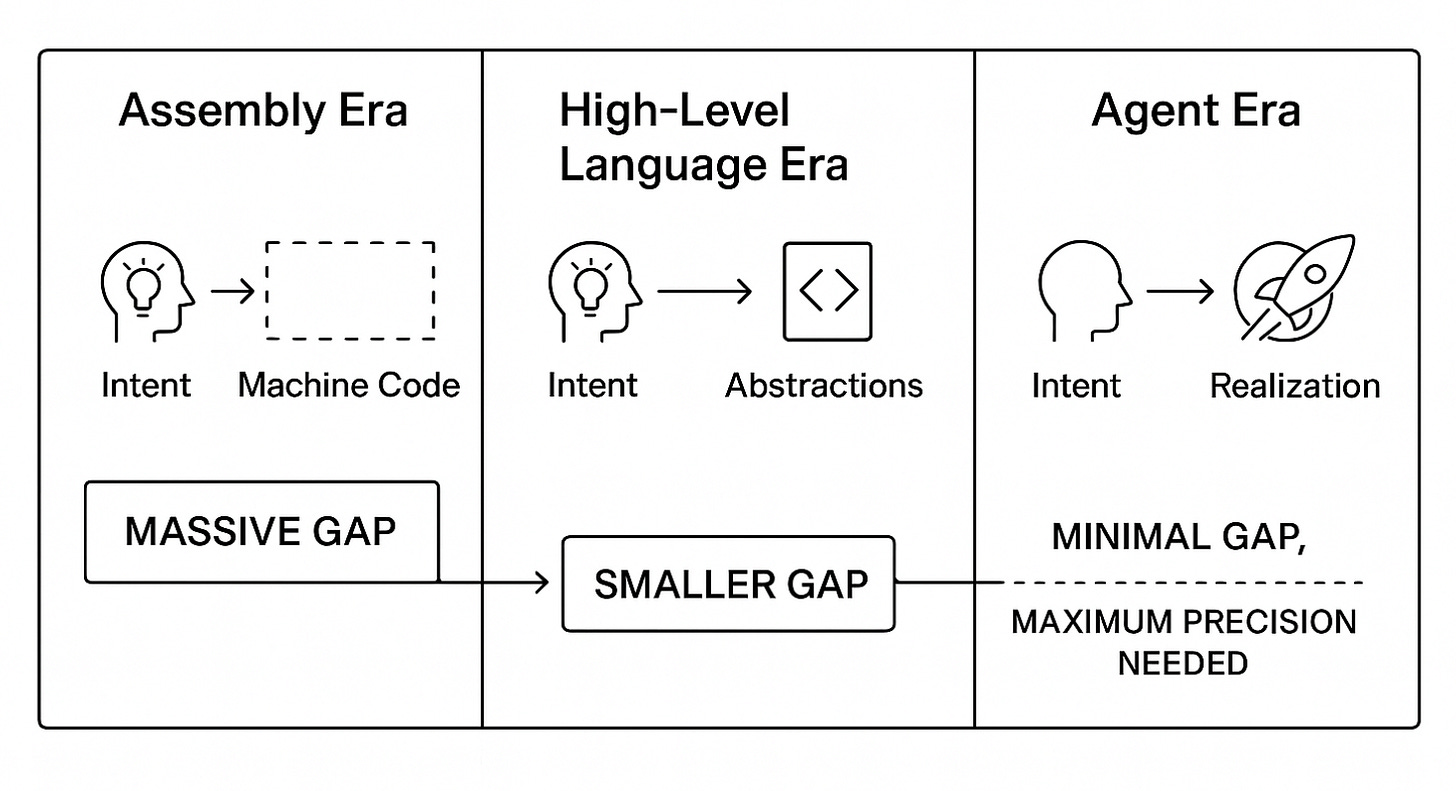

Assembly Era: Intent → Machine Code (massive gap)

High-Level Language Era: Intent → Abstractions → Implementation (smaller gap)

Agent Era: Intent → Realization (minimal gap, maximum precision needed)

The gap shrinks but the importance of intent clarity explodes given its ability to realized so quickly.

Roadmaps are Intent Debt Instruments

Even our planning tools carry intent debt.

That beautiful roadmap you presented last quarter? Compare it to what actually shipped. The divergence isn’t just about failed execution, no: it’s about intent drift.

Each item on a roadmap is a promise about future intent.

But intent, like everything else, changes.

Markets shift. Users evolve. Technical possibilities expand. The roadmap becomes a historical document of what we thought we wanted, not what we need.

So what do we do about this? How will we build organizations that minimize The Intent Gap?

Make Intent Explicit and Possible to Revisit: Not just what we’re building, but why. And not buried in a wiki, but living, breathing, and constantly questioned. As part of the software and its “source” itself.

Shorten the Feedback Loops The faster you can validate whether built reality matches intended purpose, the smaller the gap can grow.

Embrace Intent Refactoring Just as we refactor code, we will need to refactor the upstream intent. Regular review sessions in the near future will be about asking: “Is this still what we meant to build?” And can we reconcile the intent to regenerate what now diverges?

Build Intent Artifacts In our work at SpecStory, we’re exploring how to capture not just specifications but the reasoning, the context, the why behind every decision that turns into code. We believe artifacts will become the core backbone that exists to serve all future AI native builders.

I firmly believe our tools — the agents and models underneath them — WILL get better at perfectly implementing our specifications.

But in parallel the COST of misaligned intent will skyrocket.

When implementation was mostly human driven we had natural checkpoints. Slower implementation made space and time for intent to be clarified. User and customer expectations were DIFFERENT.

Now with agents that can build in hours what used to take months, we can create perfectly implemented wrong things at unprecedented scale.

Do external things distract you? Then make time for yourself to learn something worthwhile; stop letting yourself be pulled in all directions. But make sure you guard against the other kind of confusion. People who labor all their lives but have no purpose to direct every thought and impulse toward are wasting their time… even when hard at work. —II. 7

What This Means for All of Us

The future belongs not just to those who can specify most precisely but also to those who can reason most clearly about intent.

This is why prompt engineering is a temporary discipline. Despite the current fascination (trust me, I am fascinated) it’s not really about learning the right incantations. It’s about developing clarity of purpose and expressing it well to and with the new tools we use to build.

For engineers: this means your value shifts from implementation to technical intent verification and integrity.

For product managers: from requirement gathering and pure discovery to intent archaeology.

For designers: from interface and IA creation to intent manifestation.

And perhaps for founders: from vision setting to intent gardening.

Perfect software is impossible because perfect intent expression is impossible. We are, all of us, constantly approximating what we mean.

The question isn’t whether there’s a gap: there always will be. The question is whether we’re conscious of it. And whether we’re actively working to narrow it, and whether we’re building systems that acknowledge its existence.

So the next time you sit down to build (or to prompt an agent to build) pause.

Ask not “what do I want to build?” but “what do I want to achieve?” The difference between those questions is where the future of software lives.

In the end, all software is just crystallized intent. The clearer the intent: the better the crystal.

But clarity, like code, requires constant refactoring.

Self‑reflection (mine)

I’ve celebrated speed this past year and I’ll keep doing it. But the unlock wasn’t speed alone: it was relocating rigor to where it now belongs: intent. When I skip the intent work, my agents make my mistakes faster. When I slow down to be precise, they make my intent real. That’s the game.

Intent is the new source code. Our job is to keep it alive.

It seems like product teams are always re-inventing intent management systems. AI codegen is an amazing forcing function for us to realize that there are best practices and repeatable approaches we can use.